To say that the Gallipoli landing was controversial is an understatement. This controversy has been (and still is) fuelled by a great deal of conflicting opinion. When answering the question ‘Why did Gallipoli happen?”, many aspects need consideration. Relationships, politics, military strategy and geography all have a part to play in the answer.

British relationships influencing Gallipoli

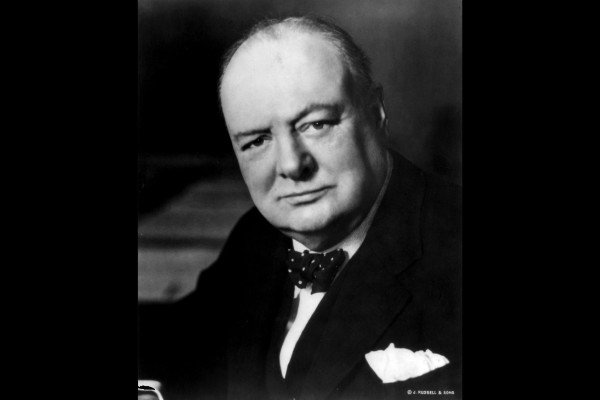

Gallipoli was labelled “Churchill’s Folly”. Many years after his death, he still receives criticism for it. The reasons behind the landing can be hard to understand. It’s easier when you explore his relationships with the leaders of the Ottoman Empire. This is the first part of unravelling the question “why did Gallipoli happen?”. Churchill first met Enver Pasha, who would become Ottoman Minister of War, in 1909. At that time, he described him as “a would-be Turkish Napoleon”. In 1910, Churchill cruised the Mediterranean on holiday. He sailed into Constantinople (now known as Istanbul). While there, he met Mehmed Djavid Bey (who became the Ottoman Minister of Finance). He also met Talaat Bey Pasha (who became the Ottoman Grand Vizier). The three of them began to correspond.

Their relationship grew. During the Libyan War, Djavid Bey wrote to Churchill with a request. He wanted to discuss the prospects of forming an alliance between their two empires. This was not the first time that the Turks had sought an alliance with Britain. Churchill welcomed the proposal. The British Foreign Secretary, Edward Grey, overruled it. For Britain, the advantages of an alliance with the Ottomans were outweighed by risk. They didn’t want to have to prop up the empire, which was crumbling. An alliance with Constantinople would also muddy the new alliance between Russia and Britain. Russia was the traditional foe of the Ottomans.

Edward Grey’s veto put the relationship under strain. The strain was increased when Churchill requisitioned two ships that the British had been contracted to build for the Ottoman navy. This was considered a slight by Enver Pasha. Churchill wrote to him to explain his actions but the explanation was not acknowledged. It has been surmised that this was because Enver Pasha had signed a treaty with the Germans the day before the Allies took his ships.

The politics behind the question: “Why did Gallipoli happen?”

Germany was much more amenable to an Ottoman alliance, particularly as war became imminent. Berlin had been constructing a railway across Ottoman territory to Baghdad since 1904. This railway would provide free access to and from ports and oil fields in Iraq (then known as Mesopotamia). A German/Ottoman alliance would secure the Berlin-to-Baghdad railway, and give Germany some control over the Bosphorus. Land access to northern Africa and the Middle East would also result. After signing the treaty with Germany, Ottoman action was not immediate. Ottomans did not formally enter World War I until late October when their fleet moved into the Black Sea and started bombing Russian ports there. The push for an Allied attack on the Ottoman Empire arrived in late 1914. The Western Front was locked in a stalemate, and Allied commanders (Churchill among them) argued for the opening of a ‘second front’ against the Ottomans and Austro-Hungarians, who they considered weaker.

The strategic value of Gallipoli

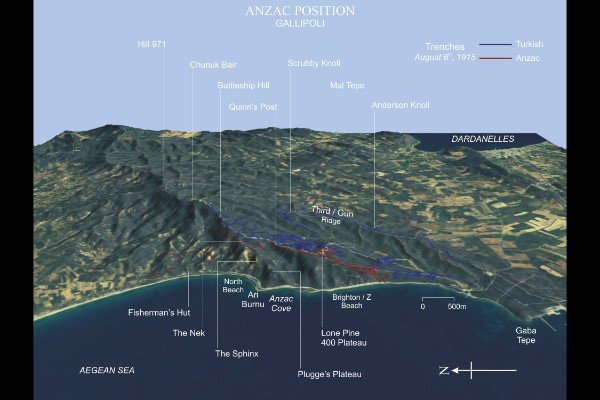

An initial attempt by the British-French force to take Turkey was made by sea. In February 1915, a fleet comprised of 18 battleships tried to force its way through to Constantinople. It did not succeed. The Allied commanders then decided to try and capture the Gallipoli Peninsula by land. There was immense strategic value for the Allies if they could capture Gallipoli. This is a critical part of answering “Why did Gallipoli happen?”. Controlling the Gallipoli Peninsula would mean the Allies could also control the strategically important Dardanelles. The Dardanelles opened up to the Sea of Marmara and ultimately the Black Sea. Controlling the Dardanelles would give Allied ships a clear run to the Sea of Marmara and the Bosphorus, where they could attack Constantinople. The Dardanelles were an important communications link with Russia for the Allies. They were also key transport and trading routes. Allied ships would have a clear run through if they were successful in landing at Gallipoli. It was also hoped that in capturing Constantinople, the allies could knock Turkey out of the way. Churchill was made bolder by knowing that there were still some British sympathisers among the Turkish ranks. He felt that if he could prove he was serious about Britain securing Constantinople, these sympathisers may launch a coup.

Why was Australia so heavily involved?

Once the decision was pushed through, an Allied invasion force was (some say hastily) organised. One of the reasons that Australia often asks “Why did Gallipoli happen?” is due to the high Australian death toll in this bloody battle. There is often talk of colonial troops being considered by British Allied commanders as being ‘less valuable’ than British troops. Many feel that they were pointlessly pushed into the battlefield as cannon-fodder, as was portrayed in the movie ‘Gallipoli’. The truth is somewhat less sinister. Allied generals at the time embroiled in battle weren’t keen to divert British men from the Western Front. This was due to its strategic importance. Because of this, the invading force was made up of British troops who had been in the Middle East, as well as French troops deployed from Africa. Their numbers were bolstered by troops hailing from the colonies. France’s troops included Senegalese. British troops included Australians, New Zealanders, Newfoundlanders, Irishmen, Welshmen, Scots, Indians and Gurkhas.

Officially speaking, 8,141 Australians died and 26,111 sustained injury at Gallipoli. Between us, the Australians and New Zealanders suffered 11,500 fatalities. This was, in fact, a fraction of the 120,000 British casualties (34,000 deaths) and 27,000 French casualties (almost 10,000 deaths). Meanwhile, it is thought the Turks sustained more than 220,000 casualties, including 85,000 deaths.

What went wrong at Gallipoli

The Ottomans caught wind of the plan to topple the empire from another location. They began to prepare for the invasion. Troops trained and drilled while defensive positions were established at important points along the Dardanelles peninsula. This area was known to the locals as Gelibolu (which is where the name Gallipoli came from). They peppered the coastline with mines. Obvious landing beaches were barricaded with barbed wire. Machine-gun nests were built upon elevated bluffs. Somewhat ignorant of this, the Allies were confident of victory. But the six-week delay between the failed naval assault and the subsequent landing would prove to be fatal. Yes, they were thinly spread and badly equipped, but the Ottomans were well established. They were also fully prepared to defend their homeland.

The Allied invasion plan was to bombard Ottoman defences by the sea with naval artillery. While this was happening, they would challenge Ottoman troops by drawing them out across several co-ordinated landing points. When the invasion began on April 25, the plan soon went awry. At two of the landing spots, the Allies were met with far stronger resistance than expected. At ‘V Beach’, troops were pelted with machine-gun fire. On the opposite side of the peninsula, Allied soldiers landed at ‘W Beach’, only to encounter the barbed wire and landmines. Ottomans manning the machine-gun nests opened fire once they came ashore. At these two beaches alone, the death toll was over 50% of the whole Gallipoli mission. Conversely, landing forces coming ashore at other points on the peninsula ambled ashore with barely any casualties. The Allied soldiers who landed at ‘S Beach’ found just 15 Ottoman soldiers defending it. At ‘Y Beach’, the coastline was bereft of Ottoman soldiers. British troops stood about on the beach, wondering what they should do next.

The most controversial moment of the Gallipoli campaign happened at ‘Z Beach’. It was northwards of a place called Gaba Tepe. The planned landing point was a wide four-mile stretch of flat sand. It is said that the boats became disoriented in the darkness of night and came to land a mile off their target. Most of the Australian and New Zealand troops came aground at a tiny inlet. Later it would become known as Anzac Cove. As the Allies swarmed ashore, Mustafa Kemal moved troops into the area. He was one of the Ottoman Empire’s most celebrated officers. They quickly set up defensive positions around the inlet. Surrounded by towering hills and dense scrub, Anzac Cove was easily defended by his snipers and machine-gunners, who held elevated positions over the cove. All Allied attempts to burst out of the area were quashed. Within just a week, the situation at Anzac Cove had arrived at a stalemate.

Why did the Anzacs evacuate?

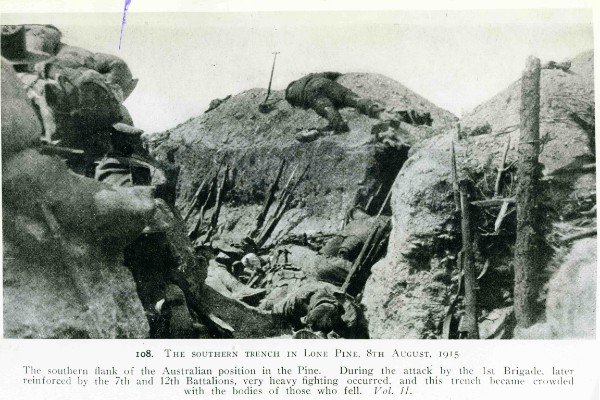

Although they were unable to move forward, the Allies kept their beach positions for nearly eight months. Further breakout attempts were made in August at Lone Pine, Chunuk Bair and The Nek. All of them failed with grave casualties, so no more offensives were contemplated. British and French forces also had no luck in advancing up the peninsula. On November 13, 1915, Field Marshal Lord Kitchener, who was Britain’s Secretary of State for War, toured the British and ANZAC lines. Just two days later, he made a recommendation to the British War Cabinet that troops be pulled out. His argument was that little progress could be made unless considerable reinforcement and a huge amount of additional artillery were put into action. Added to this, winter was approaching and continuing to deliver supplies to the area was becoming infeasible. The Australians were among the first British empire forces to evacuate the ANZAC area in December 1915. It was an operation many historians consider to be the most successful element of the entire campaign. The rest of the peninsula was evacuated by mid-January 1916.

Why do we commemorate the landings?

The Allies attempt to capture the Dardanelles was later considered to be a military disaster of the highest order. It was plagued with erroneous assumptions and bad planning. By way of contrast, Gallipoli’s defence was the Ottoman Empire’s most successful military operation during the war. Gallipoli wasn’t Australia’s first engagement in WWI. The landings were, however, the first important military action that Australian and New Zealand forces participated in during the war. Further to this, Gallipoli was the site of the first raft of major casualties. When news started filtering back to Australia, it had a massive impact. The Gallipoli campaign failed in its military objectives. Despite this, it came to symbolise the sacrifice made by those who lost their lives to war. It also created the ANZAC legend.

The date of the landings, April 25th, is of course marked by ANZAC Day. It’s an important day of remembrance in Australia and New Zealand. The first ANZAC Day was observed exactly a year after the Gallipoli landings. In cities throughout Australia, Gallipoli veterans marched, sometimes with their nurses. If they couldn’t walk, they travelled in convoys of cars. In London, Australian and New Zealander troops marched the city streets. At the Australian camp in Egypt, a sports day was organised to mark the anniversary. In Melbourne, about 380 returned Anzacs marched from Princes Bridge to a service at St Paul’s Cathedral. The following year, 400 Anzacs made the same march. By 1918, Melbourne was conducting its first big procession through the city’s streets.

It wasn’t until 1927 that every state observed an ANZAC Day public holiday. It took until the mid-1930s for the rituals such as the dawn service, ANZAC marches and two-up games to become part of our national culture. More than 100 years on, the annual remembrance of April 25 ensures that no one will forget the bravery of those Australians, nor the sacrifices they made.